|

THE WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN July 18-19, 1998 EVERLASTING LINDA |

|

Two decades after reaching her zenith as a rock star, Linda Ronstadt

is still seeking the sublime, she tells Debbie Kruger It's summer in Tucson, around 38° C, and Linda Ronstadt is sanguine about the waterlilies sprouting in her pond. The rest of the grounds are arid, bar some roses growing near the front entrance to her pink stucco house, and she plans to create an authentic Arizona garden with plenty of cacti. But she wanted waterlilies in her patch of the desert, and she's got them. Here is a woman with vision and focus. Boundless energy, too. At 52, Ronstadt seems indefatigable. She will moan with humour about parenthood (she is the single mother of two young adopted children) and with less humour about her sometimes debilitating auto-immune thyroid disease, which caused her to cancel concerts in the US last year- the first time in a 30-year career she has ever cancelled, she says. But while most pop music artists think nothing of waiting three or four years between album releases, Ronstadt has just released her 31st album in as many years, and its rock style is almost surprising, coming from someone who renounced rock 'n' roll 16 years ago and has since recorded and performed in the widest diversity of genres of any singer of her generation. She laughingly queries her decision to settle back in her home town of Tucson after so many years in California - Los Angeles for nearly 20 years, then San Francisco until last year. But Tucson is a small town and small is important to Ronstadt now after so many years of doing it big. Big album sales (her manager says around 40 million), big tours (stadiums in the 1970s, orchestras in the 80s and 90s), big awards, including nine Grammys. Her new album, We Ran, could be big, too, but Ronstadt is doing minimal publicity and her mind isn't even on the new album. It's on the next project and the three after that. And they're all small. "It's interesting to me to try to get smaller and smaller - I really believe in it, I just think it's what we should do," Ronstadt says. "I want to do the opposite of everything I've done." Despite everything she has done, Ronstadt is still best known as the 1970s queen of rock, the "kittenish" Rolling Stone cover girl, interpreter of LA songwriters' ballads and re-interpreter of hits by Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry and the Stones. The fact that eight of her nine Grammys have been awarded for work outside rock and that she has boldly experimented - and usually succeeded - in areas that would daunt most pop singers, seem to have escaped the attention of many critics.

"It was the thing I came to last in life and the hardest for me to understand," Ronstadt says of rock music. She came from a family in which every member sang, and still does, with origins in Mexican folk, German polka and waltzes, choral, operetta and opera. "Rock and roll was not my first instinct. It took me a long time to figure out how to integrate what I knew and make it my own style, because I didn't have a blues background." Although drawn to Los Angeles from Tucson in the mid-60s by forays groups such as The Byrds were making, Ronstadt never felt comfortable with the direction her career took, especially after leaving the cosy confines of the folky Troubadour Club. "The music got huge and rock and roll turned into ROCK, and it's not pleasing to listen to. It wasn't fun any more." Stadiums and huge audiences turned Ronstadt off performing, but it's not something she enjoyed anyway. She is shy on stage. She prefers recording, relishing her work in the studio. She is opinionated, greatly knowledgeable about many forms of music, and her conversation is fast and long-winded. Getting Ronstadt to stay on track requires fortitude, especially when she wants to talk about her pet topics - 18th-century glass instruments, choral music and regional music. Finally getting around to the new album, she compliments her producer, Glyn Johns, the songwriters (including Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Doc Pomus and Waddy Wachtel) and the players (members of Tom Petty's band, The Heartbreakers, and guitarists Wachtel and Bernie Leadon), but is mostly critical of her own vocal work. "What I set out to do was a rock and roll record that was more footed in the period between 1948 and 1954 or 56. And I was going to have it be the original rock and roll thing, when it just crawled out from saloon songs and from doo-wop, and it was sax-driven and acoustic-based," Ronstadt explains. "That sax player who I played with on the Nelson [Riddle] things, Plas Johnson, is the guy for early rock and roll ... and I set out to make a record with Plas and some other guys. And I started recording, but I was too sick. So I just called my friend Glyn Johns." Johns's credits include The Eagles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Eric Clapton and Stevie Nicks. It quickly became an electric guitar-sounding album. "I'd never worked with Glyn before, I'd heard he kind of has a tendency to take over and I never would have been able to work with someone like him before. I was really surprised at quite how much he did take over, but I decided to let him ... "Glyn does things completely the opposite from the way that I do them. I craft things, I sweat over them, I take a long time. He just records them and says, 'Get on with it', and some of me doesn't agree with that. I'm a better singer when I have time with my vocals." The results on We Ran, however, are unmistakably Ronstadt, and arguably the most accessible, sophisticated rock music she has recorded. And the vocals, her criticism notwithstanding, are strong and sublime. To Ronstadt, sublime is something else. It's the glass armonica, an instrument she was first captivated by in the early 1970s. "I don't remember to this day where I first heard it, but I never heard music the same after that. It was one of those experiences that just changes everything. And I searched for it always after that, but I wasn't on a track that would run me into a glass armonica, I was on a track that would run me into a guitar player." Finally, in 1993, when Ronstadt was commissioned to write and record a song for Agnieszka Holland's film, The Secret Garden, she knew the time had come to find a glass armonica. Although she didn't discover her armonicist, Dennis James, until after the track, Winter Light, was cut, she incorporated his playing into the revamped version of the song for her album of the same name, and used him on three successive albums, most noticeably Dedicated To The One I Love, her 1996 collection of rock songs reinterpreted as children's lullabies. One of her next projects will be to produce an album of glass music for Sony's classical label. She also intends to incorporate glass instruments into her upcoming Christmas choral record. Ronstadt hopes to team up with different vocal ensembles, from San Francisco's Chanticleer to the order of Benedictine nuns in the chapel around the corner from her house in Tucson. That, to her, is sublime. Sublime is also how Ronstadt refers to the voice of Emmylou Harris, her "singing sister", with whom she is working on two other projects: a second Trio album, also featuring Dolly Parton (it was recorded several years ago, but never released due to differences with Parton) and an album of new works featuring artists sucn as French-Canadian singer-songwriters Kate and Anna McGarrigle. And sublime is opera. Ronstadt went to Broadway in the early 80s to star in Joseph Papp's productions of Pirates of Penzance and La Boheme. She says she could have had a career in opera had she chosen that direction when she was 17. One of her biggest thrills was singing O Soave Fanciulla with Placido Domingo. "It was beautiful, and I just had a great time doing it, but I knew I was over my head." Ronstadt also felt out of her league when she began working with Nelson Riddle on what turned out to be a trilogy of albums featuring jazz and Broadway standards. But she was gratified Riddle had the chance, before his death, to reaffirm the importance of the music to which he had devoted his life. "All of that style of music was just so brutally cast aside by rock and roll, and I think he felt that he had reasserted that what they did was finer."

Her contributions to the work of other artists include vocals for Paul Simon's Graceland, Randy Newman's Faust and two Philip Glass albums; producing for Webb, Aaron Neville and David Lindley; and harmonies on a multitude of recordings by friends and colleagues. And when she's done with glass, choirs and Emmylou, she'll set new goals. "It's very important for me not to have my middle age be a repeat of my youth, and my old age to not be a repeat of my middle age," Ronstadt says. "I know there are certain things that I must do so that I won't be kept awake late at when I'm in my 60s and 70s saying, 'I wish I'd done that'." At least growing waterlilies in the desert won't be one of those things. |

Fortunately, Ronstadt doesn't give a damn. "I've decided that I'll do whatever I want to do

and I've always tried not to have commercial considerations, but they were considered for me

even more than I might have done on my own ... I wasn't always real satisfied with the music

I made," she says, referring to the string of multi-million-selling albums she released

in the 70s.

Fortunately, Ronstadt doesn't give a damn. "I've decided that I'll do whatever I want to do

and I've always tried not to have commercial considerations, but they were considered for me

even more than I might have done on my own ... I wasn't always real satisfied with the music

I made," she says, referring to the string of multi-million-selling albums she released

in the 70s.

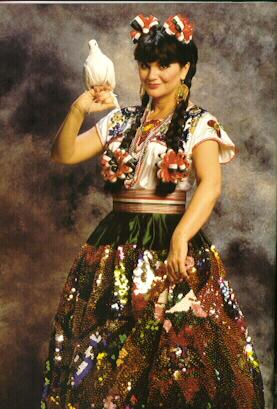

Ronstadt's reverence for the songwriter has been evident throughout her career. Jimmy Webb

is her favourite contemporary songwriter, but on top are George and Ira Gershwin. The desire to

work with good songs was what compelled her to record a string of Mexican albums and perform

mariachi concerts in full costume. Today she still gets together with family members

to sing Mexican folk songs.

Ronstadt's reverence for the songwriter has been evident throughout her career. Jimmy Webb

is her favourite contemporary songwriter, but on top are George and Ira Gershwin. The desire to

work with good songs was what compelled her to record a string of Mexican albums and perform

mariachi concerts in full costume. Today she still gets together with family members

to sing Mexican folk songs.