Linda Ronstadt enters the press room at a trade magazine's office in Los Angeles with her five-person

entourage, and immediately manages to find familiar territory in a roomful of strangers. She chats

up retailers, fans, and critics on their own terms and leaves each of them feeling like they've

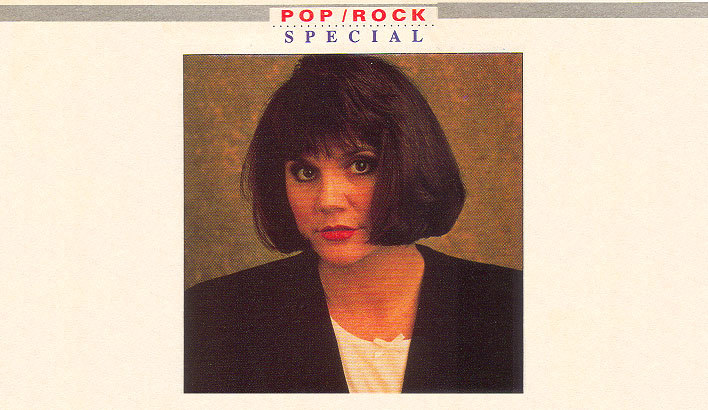

shared common ground. As one of America's most famous and enduring female pop vocalists, Ronstadt

understands what people are made of and how to hit their emotional bull's-eye every time, whether

it's through light and sprightly talk, probing interviews, or songs invested with the depth of her experiences.

Recordings such as Heart Like a Wheel, Don't Cry Now, Hasten Down the Wind,

Prisoner in Disguise, and Livin' in the U.S.A. established Ronstadt as America's rock'n'roll

sweetheart. Later forays into new wave (Mad Love), American jazz standards (three recordings with

Nelson Riddle), and Mexican mariachi (Canciones de mi Padre) pushed pop's limits and broadened

our musical horizons.

Now Ronstadt has returned to pop with a mature release that recalls why and how we all fell in love

with the voice that embodies all the raw, aching emotions and vulnerabilities of a broken heart. Cry Like

a Rainstorm, Howl Like the Wind features a collection of songs from some of America's best songwriters,

including Karla Bonoff ("Trouble Again"), Jimmy Webb ("Adios," "Still Within the Sound of My Voice"), and the

team of Paul Carrack/Nick Lowe/Martin Belmont ("I Need You"). The disc also boasts New Orleans' silk-voiced

Aaron Neville on four duets; Brian Wilson singing backup harmonies on "Adios"; the Tower of Power horn section

on "When Something Is Wrong with My Baby"; and the Skywalker Symphony Orchestra, a group of musicians from

northern California.

Ronstadt recently spoke to CDR to discuss the making of the album.

CDR: It's nice hearing you sing pop again.

Linda Ronstadt: I enjoyed making Cry Like a Rainstorm. I got to work with a lot of my favorite

people, and I got to meet some new people. The Tower of Power horn section- I'd always wanted to work

with them. And Brian Wilson- he came into the studio and sang 15 parts for "Adios"! I was just

flabbergasted. Brian's really a vocal orchestrator. There isn't anybody else in pop music with that kind

of talent. He just comes in and puts the parts down, one right after another- real close, intricate harmony

parts. I was astounded.

CDR: How did you two get hooked up?

Ronstadt: I knew him years ago. I think we met at the Troubadour and became friends. He lived not

too far from me, when I was living above the Sunset Strip. He used to come knock on my door on a regular

basis, usually on the way to the health food store- I think everybody was drinking grape juice in those days.

Sometimes he'd be short of money and he'd come to my back door and say, "I need to borrow 18 cents." He'd get

a couple bottles of grape juice and come back and we'd drink it together. He wasn't living at home at that

point and he was having a hard time adjusting to things like doing his laundry. We'd go sit in the laundromat

and watch the clothes go 'round and talk about rock'n'roll. I was hoping he'd remember those times as fondly

as I did- and he does.

CDR: Aaron Neville also played a big part on the album.

Ronstadt: He's just the guy every singer wants to sing with. When I went to New Orleans a few years

ago with Nelson Riddle and my jazz band, the first thing we wanted to do, naturally, was find the Neville

Brothers. When we found out where they were playing, Aaron was on stage singing. I had no idea he even

knew who I was, but he invited me up. Normally I don't like to do those kind of things because I like to

rehearse, but I just couldn't resist.

So I was up there singing doo-wop songs with him, and because we sing in kind of the same key, I thought

we sounded good together. Then I thought, "Of course you sound good with him. Every singer thinks he

sounds good singing with Aaron Neville. A typist would come away thinking that it was a perfect duet."

I was surprised and delighted when he called and asked if I'd like to come sing with him on the New Orleans

Against the Hungry and Homeless benefit he does every year. I ran right back there and the first song we worked

up, because we knew all the words, was Schubert's "Ave Maria." Something I'd always wanted to sing was

"When Something's Wrong with My Baby," so we worked that out. That was the beginning, the seed of our duet.

But it took me a while to work up my nerve to ask him to record with me. There was a lot of hand wringing

and sweating involved. But he said yes right away, and I was thrilled.

We kept in close contact for the next two or three years and suggested songs back and forth. It's

amazing how long projects take from the idea to actually having the package in hand. I get an idea and think,

"Oh, I'm going to do that tomorrow," but I don't get to it for two or three years.

CDR: Is preparing for a record more involved than making it?

Ronstadt: Let me answer that with an example. People ask me, "What do you listen to on the radio?"

Well, I don't listen to the radio. I listen to composite cassette tapes of whatever I'm trying to learn at

the time. For three years, I listened to nothing but Mexican music, whether I was driving around in my car

or taking a bath. I really steeped myself in it. Of course, I'd grown up with it, too. I could sing it

as an amateur, but I couldn't sing it as a professional until I worked on it.

The thing that prepared me for working with Aaron was singing with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris.

Dolly's got that kind of Appalachian authenticity to her style...

CDR: That purity...

Ronstadt: That's as pure as it gets. Emmy and I have always been kind of in awe of her, so to try

and learn to sing with her, to try and emulate it, is like being on a rollercoaster, because you're just kind

of going along with her. It's exhilarating because you get to experience the music almost from inside her soul.

It's like looking out at the music through her eyes.

I did things vocally with Dolly that I could never do on my own. I could never sing a song like Dolly does,

because the kind of vocal embellishment she does doesn't come naturally to me. But I can shadow it and ride

along with her-- outline and embellish her voice.

It was the same thing with Aaron. I learned to do a lot of things with him I wouldn't have ever been able

to do myself, because I'm not a New Orleans singer, and I'm certainly not an R&B singer. I grew up in

Tucson, AZ, and I'm the product of a very random musical environment, basically because of the radio.

We lived where you could get station XERF in Del Rio, TX. They played every kind of music there was.

I got all the country and bluegrass music, all the gospel, all the rock'n'roll... But at home, I got Gilbert &

Sullivan, Mexican music, opera, and American jazz standards. So all that was really authentic to my musical

base. Yet people always say, "Well, you're doing something new again." Actually, I'm not; I'm doing something old!

As a singer, I came to rock'n'roll relatively late in life. I didn't start hearing rock on the radio until I

was 7, and I didn't start trying to sing it till I was a teenager- and a late teenager at that. I was also trying

to sing folk music, and I was listening to bluegrass and Bill Monroe, and I just loved it. My brother and sister

and I would try to sing those harmonies, and we'd also try to sing three-part Mexican harmonies.

CDR: You do a lot of Jimmy Webb songs on this record.

Ronstadt: His stuff consistently has been recorded by good artists. Certainly you can't get a a higher

compliment than having someone like Ray Charles recording your work. But Jimmy has been overlooked. I think it's

that "hip" thing- that glib Rolling Stone reductionist attitude that's done no good to pop music. In fact,

it's done a great deal of harm in terms of making people self-conscious about their music and about other people's

opinions, because [Rolling Stone's critics] write from such an insecure vantage point. It's that kind of

attitude that tends to discount the things Jimmy's done, which aren't very trendy. He's real sensitive because he

took a lot of battering in the '60s, when that hipper-than-thou thing was going on. Meanwhile, all these artists

were admiring Jimmy's music. Get Don Henley and J.D. Souther and Jackson Browne in the corner of the El Adobe Cafe

and they'd be talking about what a great songwriter Jimmy Webb is and how they wish they had the guts to write

a song that rhymes "adios," "morose," and "grandiose."

Anyway, these were songs I'd had around for a long time. They were like a dog on my heels. I'd listen to them

over and over and over again, but I didn't have the confidence to address them. After I got through singing with

Dolly and Emmy, and doing Mexican music, I felt like maybe I could take on those Jimmy Webb songs.

In fact, I really went to "phrasing school" for this album. If I didn't know something, I just asked somebody

who did. For "Cry Like a Rainstorm, Howl Like the Wind," a song I've known for a long time, I just got overwhelmed.

I called [Little Feat's] Craig Fuller and said, "Look, you really know how to sing this. Come and help me." He came

into the studio, and we went through track after track of vocals and listened to different interpretations. We sat

at the piano and by the time we went through it again and again, I had a road map and knew how to get through it.

CDR: How'd you come to the Paul Carrack material?

Ronstadt: Danny Ferrington, my roommate- and a wonderful guitar maker- loves Paul Carrack's songs.

He just kept bugging me about him for such a long time that I finally took his word for it. "I Need You" was a song

I'd suggested for Smokey Robinson because he wanted to do a duet with me, but he just didn't hear it. So I kept

it on hold because I knew it would be a great duet some day.

CDR: It's probably difficult to define, but what is making music all about for you?

Ronstadt: Music is aural dreaming. You're dreaming in sound- and the function that art serves for me

is to make order out of chaos, to make sense out of life. Life is relentless; it's often senseless and painful.

Music provides us with these certain classic patterns that repeat and evolve and reorganize themselves on an infinite scale.

And that's what I use it for.

If you sit down and say, "I'm going to make a hit record," you can't do it. Music should unscramble those emotions

of "Someone hurt my feelings," or "Someone made me feel good," or "I was hoping for this but I got disappointed."

It can be very restoring, renewing, and life-giving. Therein lies the secret of its spiritual nature. I'm not religious- that

may be the understatement of the century. But I feel like I'm spiritual because I sing- not that you have to sing to be spiritual.

What music proves to me beyond any shadow of a doubt is that we all have a spiritual side to us. We all have the ability to

have those feelings evoked within us.