NEW TIMES

Oct. 14, 1977

LINDA RONSTADT:

HER SOFT-CORE CHARMS

by John Rockwell

Thanks to Rob Willhoit for providing this article.

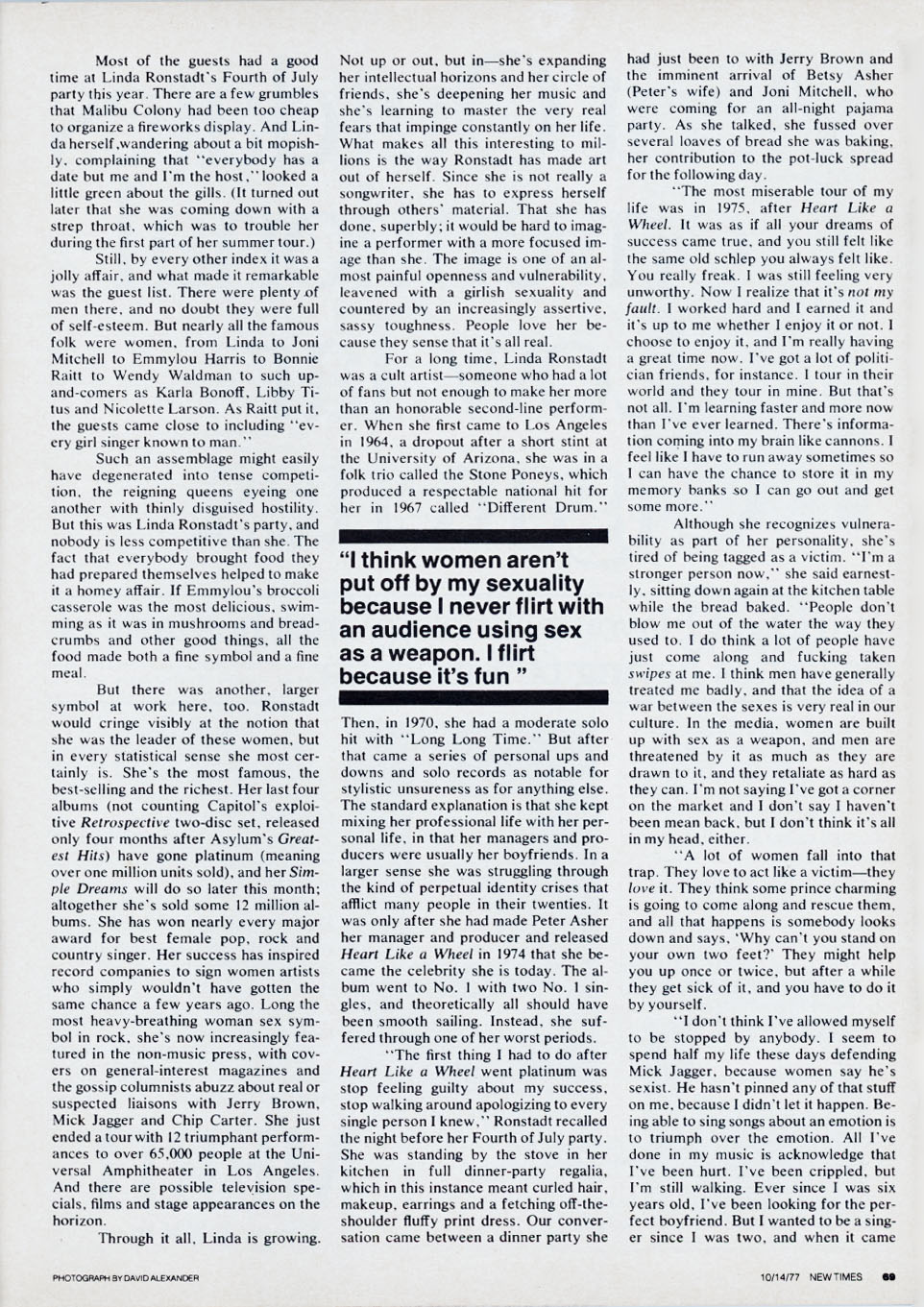

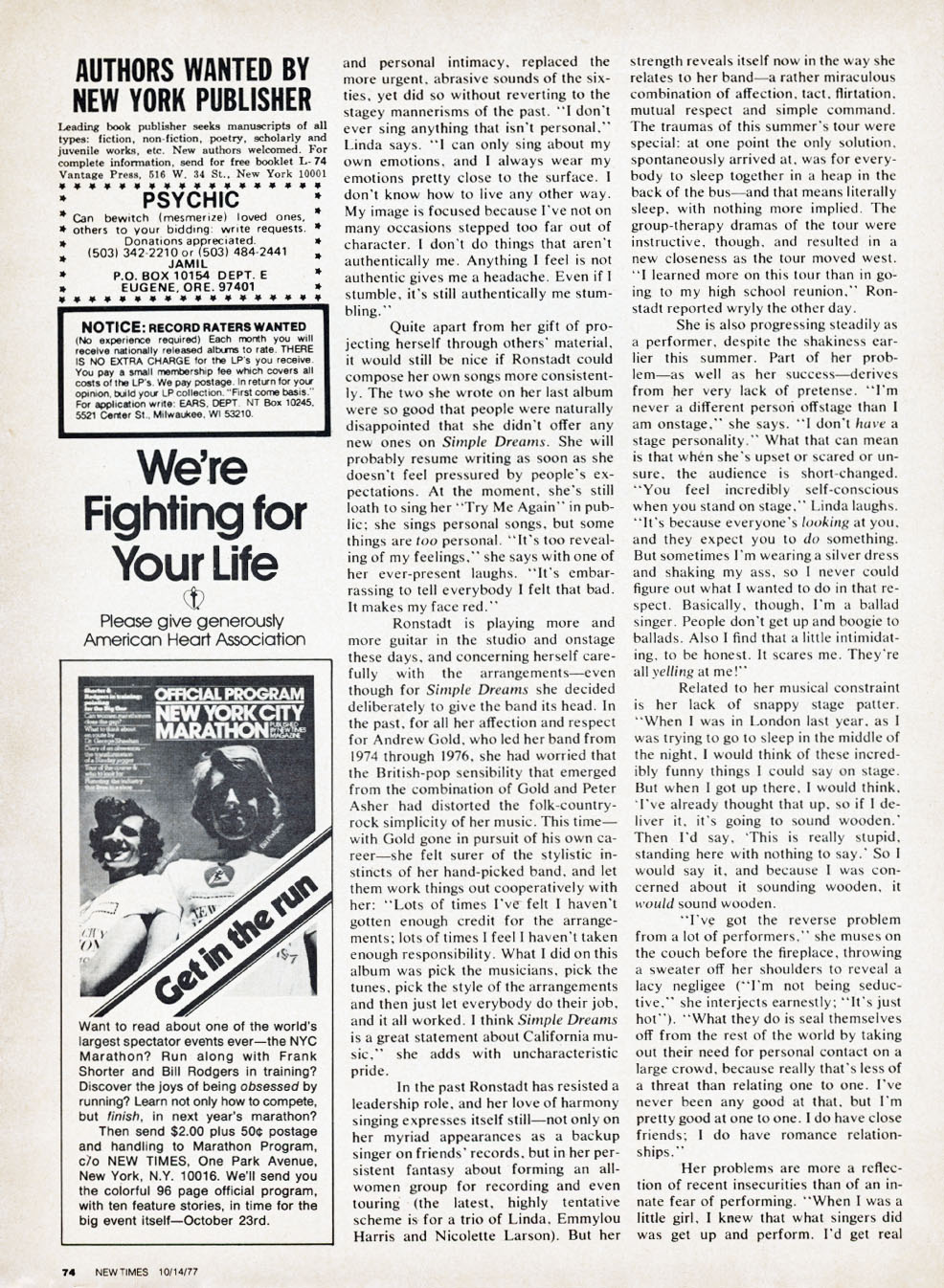

Most of the guests had a good time at Linda Ronstadt's Fourth of July party this year. There are

a few grumbles that Malibu Colony had been too cheap to organize a fireworks display. And Linda

herself, wandering about a bit mopishly, complaining that "everybody has a date but me and I'm

the host," looked a little green about the gills. (It turned out later that she was coming down

with a strep throat, which was to trouble her during the first part of her summer tour.)

Still, by every other index it was a jolly affair, and what made it remarkable was the guest

list. There were plenty of men there, and no doubt they were full of self-esteem. But nearly

all the famous folk were women, from Linda to Joni Mitchell to Emmylou Harris to Bonnie Raitt to

Wendy Waldman to such up-and-comers as Karla Bonoff, Libby Titus and Nicolette Larson. As Raitt

put it, the guests came close to including "every girl singer known to man."

Such an assemblage might easily have degenerated into tense competition, the reigning queens

eyeing one another with thinly disguised hostility. But this was Linda Ronstadt's party, and

nobody is less competitive than she. The fact that everybody brought food they had prepared

themselves helped to make it a homey affair. If Emmylou's broccoli casserole was the most

delicious, swimming as it was in mushrooms and breadcrumbs and other good things, all the food

made both a fine symbol and a fine meal.

But there was another, larger symbol at work here, too. Ronstadt would cringe visibly at the

notion that she was the leader of these women, but in every statistical sense she most certainly

is. She's the most famous, the best-selling and the richest. Her last four albums (not counting

Capitol's exploitive Retrospective two-disc set, released only four months after Asylum's

Greatest Hits) have gone platinum (meaning over one million units sold), and her

Simple Dreams will do so later this month; altogether she's sold some 12 million albums.

She has won nearly every major award for best female pop, rock and country singer. Her success

has inspired record companies to sign women artists who simply wouldn't have gotten the same

chance a few years ago. Long the most heavy-breathing woman sex symbol in rock, she's now

increasingly featured in the non-music press, with covers on general-interest magazines and the

gossip columnists abuzz about real or suspected liaisons with Jerry Brown, Mick Jagger and Chip

Carter. She just ended a tour with 12 triumphant performances to over 65,000 people at the

Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles. And there are possible television specials, films and

stage appearances on the horizon.

Through it all, Linda is growing. Not up or out, but in- she's expanding her intellectual

horizons and her circle of friends, she's deepening her music and she's learning to master the

very real fears that impinge constantly on her life. What makes all this interesting to

millions is the way Ronstadt has made art out of herself. Since she is not really a songwriter,

she has to express herself through others' material. That she has done, superbly; it would be

hard to imagine a performer with a more focused image than she.

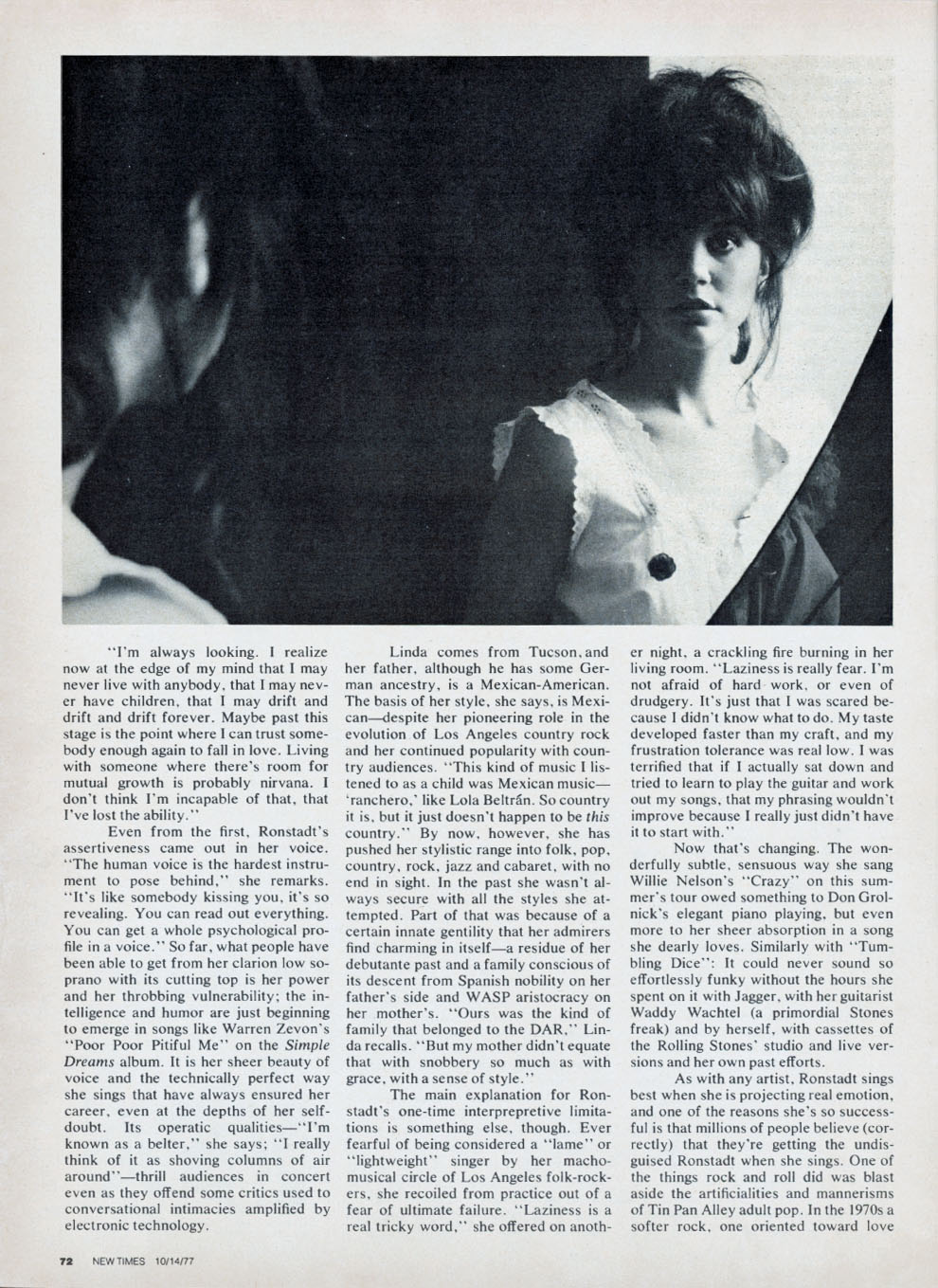

The image is one of an almost painful openness and vulnerability, leavened with a girlish

sexuality and countered by an increasingly assertive, sassy toughness. People love her because

they sense that it's all real.

For a long time, Linda Ronstadt was a cult artist- someone who had a lot of fans but not

enough to make her more than an honorable second-line performer. When she first came to Los

Angeles in 1964, a dropout after a short stint at the University of Arizona, she was in a folk

trio called the Stone Poneys, which produced a respectable national hit for her in 1967 called

"Different Drum."

Then, in 1970, she had a moderate solo hit with "Long Long Time." But after that came a series

of personal ups and downs and solo records as notable for stylistic unsureness as for anything

else. The standard explanation is that she kept mixing her professional life with her personal

life, in that her managers and producers were usually her boyfriends. In a larger sense she was

struggling through the kind of perpetual identity crises that afflict many people in their

twenties. It was only after she had made Peter Asher her manager and producer and released

Heart Like a Wheel in 1974 that she became the celebrity she is today. The album went to

No. 1 with two No. 1 singles, and theoretically all should have been smooth sailing. Instead,

she suffered through one of her worst periods.

"The first thing I had to do after Heart Like a Wheel went platinum was stop feeling

guilty about my success, stop walking around apologizing to every single person I knew," Ronstadt

recalled the night before her Fourth of July party. She was standing by the stove in her kitchen

in full dinner-party regalia, which in this instance meant curled hair, makeup, earrings and a

fetching off-the-shoulder fluffy print dress. Our conversation came between a dinner party she

had just been to with Jerry Brown and the imminent arrival of Betsy Asher (Peter's wife) and Joni

Mitchell, who were coming for an all-night pajama party. As she talked, she fussed over several

loaves of bread she was baking, her contribution to the pot-luck spread for the following day.

"The most miserable tour of my life was in 1975, after Heart Like a Wheel. It was as

if all your dreams of success came true, and you still felt like the same old schlep you always

felt like. You really freak. I was still feeling very unworthy. Now I realize that it's

not my fault. I worked hard and I earned it and it's up to me whether I enjoy it or not.

I choose to enjoy it, and I'm really having a great time now. I've got a lot of politician

friends, for instance. I tour in their world and they tour in mine. But that's not all. I'm

learning faster and more now than I've ever learned. There's information coming into my brain

like cannons. I feel like I have to run away sometimes so I can have the chance to store it in

my memory banks so I can go out and get some more."

Although she recognizes vulnerability as part of her personality, she's tired of being tagged

as a victim. "I'm a stronger person now," she said earnestly, sitting down again at the kitchen

table while the bread baked. "People don't blow me out of the water the way they used to. I do

think a lot of people have just come along and fucking taken swipes at me. I think men

have generally treated me badly, and that the idea of a war between the sexes is very real in our

culture. In the media, women are built up with sex as a weapon, and men are threatened by it as

much as they are drawn to it, and they retaliate as hard as they can. I'm not saying I've got a

corner on the market and I don't say I haven't been mean back, but I don't think it's all in my

head, either.

"A lot of women fall into that trap. They love to act like a victim- they love it.

They think some prince charming is going to come along and rescue them, and all that happens is

somebody looks down and says, 'Why can't you stand on your own two feet?' They might help you up

once or twice, but after a while they get sick of it, and you have to do it by yourself.

"I don't think I've allowed myself to be stopped by anybody. I seem to spend half my life

these days defending Mick Jagger, because women say he's sexist. He hasn't pinned any of that

stuff on me, because I didn't let it happen. Being able to sing songs about an emotion is to

triumph over the emotion. All I've done in my music is acknowledge that I've been hurt. I've

been crippled, but I'm still walking. Ever since I was six years old, I've been looking for the

perfect boyfriend. But I wanted to be a singer since I was two, and when it came right down to

it, I would never give up the singing for any old boyfriend."

That hardly means that Linda Ronstadt has, at 31, turned into a tough, career-minded woman

who's put her emotional troubles behind her. People who respond to the pain and passion of her

ballads can rest assured that there's still plenty of turmoil left to inspire her.

Take the tour that just ended, for instance. Before it began in early August, she was eager

to get out on the road again. She hadn't performed for six months and she was full of

confidence about her evolving performing skills. At 107 pounds, she was at her lowest weight

in years, and she usually feels good when she's thin. She was proud of her new band, and, as she

put it ruefully a few weeks later in a late-night telephone call, "it was going to be rock and

roll forever."

It didn't work out quite that way: "It wasn't vague, neurotic meanderings that made me feel

so bad," she insisted later. "There really were things to feel bad about." Chief among them was

the state of her voice, weakened by the strep throat infection and strained by the final bit of

overdubbing on Simple Dreams (which was the repeated "You've got to roll me" at the end

of "Tumbling Dice").

"I worried myself sick," Linda said, "I wasn't able to rely on what I count on most, my

voice." In addition, there were gynecological problems, worries over gossip-column reports

about her love life, and tensions within the band- not only because it turned out to be a

particularly sensitive group of people, but because Ronstadt felt insecure about her own

musical skills with musicians she so much admired, and her own insecurities rippled out into

her entourage. "Everybody takes their cue from me," she says.

The clouds began to gather when she had a dream in Maryland about being attacked and bitten

by her favorite animals, "ducks and bunnies." It was only the next day, when a children's

petting zoo was discovered near the site of the concert, that she could allay her not-so-simple

dreams by spending a half-hour petting soft little animals. But next week in the bus, driving

from New York to Tanglewood, trouble was in the air again. Linda was uncharacteristically mute

on the way up, curled under a blanket and watching Star Wars on the video cassette. At

the show she looked tense and scared, retreating back to Ricky Marotta on drums between every

song and clearly nursing her voice by singing at half volume when she could get away with it.

The next night in Suffern, New York, it all came to a head. After the fifth song she simply

felt too weak and faint to continue, and the audience's money was refunded. She toyed with

canceling the tour and slinking back home to Malibu, but visits to a throat specialist and a

gynecologist in New York proved reassuring, as did a talk with her doctor in Los Angeles. On

the telephone she sounded shaken but determined. "We're going to take it day by day," she

said. "I really think everything in my life led to last night."

The point is, though, that she made it. "I've been reassured by this," she reported a few

days after Suffern. "The central core of my being is strong." It is a theme she's

sounded often. And it's related not only to her growing confidence in her music and her success,

but in her realization that she could live alone, not permanently tied to any one boyfriend.

Last year Karen Durbin wrote an article in the Village Voice about being a woman alone;

Linda carried it around in her purse for a month, showing it eagerly to all her women friends.

"Men give you a nasty choice," she argued at the kitchen table in Malibu. "Either you put up

with them chipping away at you emotionally, or you don't have them. Well, I've chosen not to

have them- not to live with someone. I chose to have lots of boyfriends instead of trying to pin

it all on one, and I look to myself for my own security. I don't see my life as a failure because

I live alone. I wake up sometimes and say, 'Oh my god, this is torture' But other times I

say, 'So I'm alone, so I can read.' And sometimes I wake up in the morning and I'm alone.

But I don't turn around and say, 'Look what's become of me,' because the man is always a good

friend. I don't feel I'm promiscuous particularly. I can't expect to fall in love with every

guy I go to bed with: that's just silly. But there's no reason why you can't have an intimate

relationship based on affection and tenderness and warmth and friendship- and sex. It's not

love, but it's not bad!

"I think women aren't put off by my sexuality because I never flirt with an audience using

sex as a weapon. I flirt because it's fun. It's not a sexy thing so much as spunk and

enthusiasm. I feel like the audience is involved and I'm involved. People love somebody who

has spunk. They want you to be their hero, their victor. You can use sex as a threat, or you

can use it like Dolly [Parton] uses it, as a celebration of your attractiveness, with nobody

left out.

"I find now that I'm starting to make friends with women in other professions- it used to be

that girl singers were the only professional women I knew. All my women friends encourage and

support each other. Mostly, we're all single, and we find that we're enjoying it. It's

lonely, but Jesus Christ, I was lonelier when I lived with somebody. I'm not saying it's

better. I'm just saying that living alone is better than living with someone you don't want

to live with.

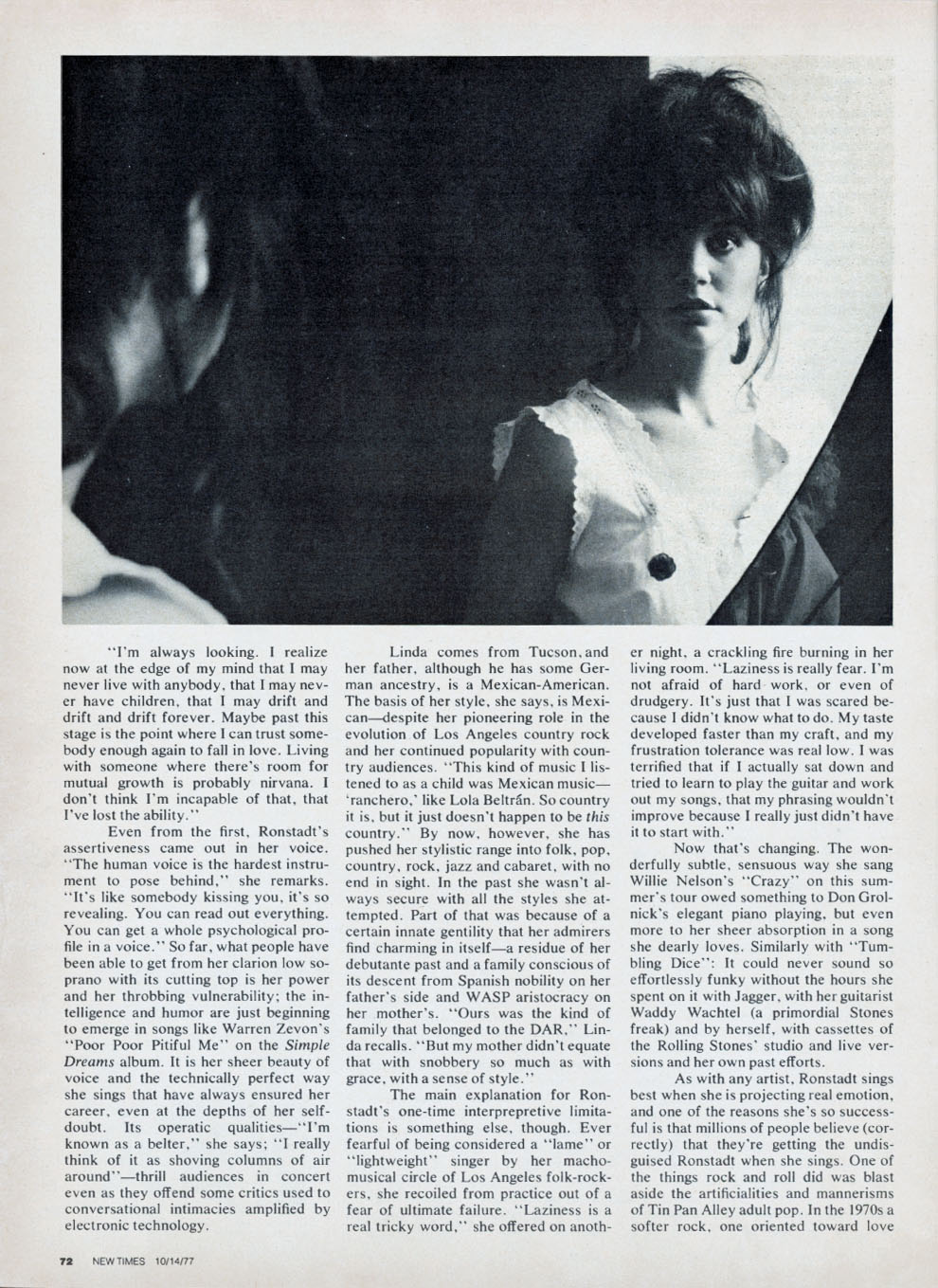

"I'm always looking. I realize now at the edge of my mind that I may never live with anybody,

that I may never have children, that I may drift and drift and drift forever. Maybe past this

stage is the point where I can trust somebody enough again to fall in love. Living with someone

where there's room for mutual growth is probably nirvana. I don't think I'm incapable of that,

that I've lost the ability."

Even from the first, Ronstadt's assertiveness came out in her voice. "The human voice is the

hardest instrument to pose behind," she remarks. "It's like somebody kissing you, it's so

revealing. You can read out everything. You can get a whole psychological profile in a voice."

So far, what people have been able to get from her clarion low soprano with its cutting top is

her power and her throbbing vulnerability; the intelligence and humor are just beginning to

emerge in songs like Warren Zevon's "Poor Poor Pitiful Me" on the Simple Dreams album.

It is her sheer beauty of voice and the technically perfect way she sings that have always

ensured her career, even at the depths of her self-doubt. Its operatic qualities- "I'm known

as a belter," she says; "I really think of it as shoving columns of air around"- thrill audiences

in concert even as they offend some critics used to conversational intimacies amplified by

electronic technology.

Linda comes from Tucson, and her father, although he has some German ancestry, is a

Mexican-American. The basis of her style, she says, is Mexican- despite her pioneering role

in the evolution of Los Angeles country rock and her continued popularity with country audiences.

"This kind of music I listened to as a child was Mexican music- 'ranchero,' like Lola

Beltrán. So country it is, but it just doesn't happen to be this country."

By now, however, she has pushed her stylistic range into folk, pop, country, rock, jazz and

cabaret, with no end in sight. In the past she wasn't always secure with all the styles she

attempted. Part of that was because of a certain innate gentility that her admirers find

charming in itself- a residue of her debutante past and a family conscious of its descent from

Spanish nobility on her father's side and WASP aristocracy on her mother's. "Ours was the kind

of family that belonged to the DAR," Linda recalls. "But my mother didn't equate that with

snobbery so much as with grace, with a sense of style."

The main explanation for Ronstadt's one-time interprepretive limitations is something else,

though. Ever fearful of being considered a "lame" or "lightweight" singer by her

macho-musical circle of Los Angeles folk-rockers, she recoiled from practice out of a fear of

ultimate failure. "Laziness is a real tricky word," she offered on another night, a crackling

fire burning in her living room. "Laziness is really fear. I'm not afraid of hard work, or

even of drudgery. It's just that I was scared because I didn't know what to do. My taste

developed faster than my craft, and my frustration tolerance was real low. I was terrified

that if I actually sat down and tried to learn to play the guitar and work out my songs,

that my phrasing wouldn't improve because I really just didn't have it to start with."

Now that's changing. The wonderfully subtle, sensuous way she sang Willie Nelson's "Crazy"

on this summer's tour owed something to Don Grolnick's elegant piano playing, but even more to

her sheer absorption in a song she dearly loves. Similarly with "Tumbling Dice": It could never

sound so effortlessly funky without the hours she spent on it with Jagger, with her guitarist

Waddy Wachtel (a primordial Stones freak) and by herself, with cassettes of the Rolling Stones'

studio and live versions and her own past efforts.

As with any artist, Ronstadt sings best when she is projecting real emotion, and one of the

reasons she's so successful is that millions of people believe (correctly) that they're getting

the undisguised Ronstadt when she sings. One of the things rock and roll did was blast aside

the artificialities and mannerisms of Tin Pan Alley adult pop. In the 1970s a softer rock, one

oriented toward love and personal intimacy, replaced the more urgent, abrasive sounds of the

sixties, yet did so without reverting to the stagey mannerisms of the past. "I don't ever sing

anything that isn't personal," Linda says. "I can only sing about my own emotions, and I always

wear my emotions pretty close to the surface. I don't know how to live any other way. My image

is focused because I've not on many occasions stepped too far out of character. I don't do

things that aren't authentically me. Anything I feel is not authentic gives me a headache.

Even if I stumble, it's still authentically me stumbling."

Quite apart from her gift of projecting herself through others' material, it would still be

nice if Ronstadt could compose her own songs more consistently. The two she wrote on her last

album were so good that people were naturally disappointed that she didn't offer any new ones

on Simple Dreams. She will probably resume writing as soon as she doesn't feel pressured

by people's expectations. At the moment, she's still loath to sing her "Try Me Again" in public;

she sings personal songs, but some things are too personal. "It's too revealing of my

feelings," she says with one of her ever-present laughs. "It's embarrassing to tell everybody

I felt that bad. It makes my face red."

Ronstadt is playing more and more guitar in the studio and onstage these days, and concerning

herself carefully with the arrangements- even though for Simple Dreams she decided

deliberately to give the band its head. In the past, for all her affection and respect for

Andrew Gold, who led her band from 1974 through 1976, she had worried that the British-pop

sensibility that emerged from the combination of Gold and Peter Asher had distorted the

folk-country-rock simplicity of her music. This time with Gold gone in pursuit of his own

career- she felt surer of the stylistic instincts of her hand-picked band, and let them work

things out cooperatively with her. "Lots of times I've felt I haven't gotten enough credit for

the arrangements; lots of times I feel I haven't taken enough responsibility. What I did on

this album was pick the musicians, pick the tunes, pick the style of the arrangements and then

just let everybody do their job, and it all worked. I think Simple Dreams is a great

statement about California music," she adds with uncharacteristic pride.

In the past Ronstadt has resisted a leadership role, and her love of harmony singing expresses

itself still- not only on her myriad appearances as a backup singer on friends' records, but in

her persistent fantasy about forming an all-women group for recording and even touring (the

latest, highly tentative scheme is for a trio of Linda, Emmylou Harris and Nicolette Larson).

But her strength reveals itself now in the way she relates to her band- a rather miraculous

combination of affection, tact, flirtation, mutual respect and simple command. The traumas of

this summer's tour were special: at one point the only solution, spontaneously arrived at,

was for everybody to sleep together in a heap in the back of the bus- and that means literally

sleep, with nothing more implied. The group-therapy dramas of the tour were instructive, though,

and resulted in a new closeness as the tour moved west. "I learned more on this tour than in

going to my high school reunion," Ronstadt reported wryly the other day.

She is also progressing steadily as a performer, despite the shakiness earlier this summer.

Part of her problem- as well as her success- derives from her very lack of pretense. "I'm never

a different person offstage than I am onstage," she says. "I don't have a stage

personality." What that can mean is that when she's upset or scared or unsure, the audience is

short-changed. "You feel incredibly self-conscious when you stand on stage," Linda laughs.

"It's because everyone's looking at you, and they expect you to do something.

But sometimes I'm wearing a silver dress and shaking my ass, so I never could figure out what I

wanted to do in that respect. Basically, though, I'm a ballad singer. People don't get up and

boogie to ballads. Also I find that a little intimidating, to be honest. It scares me.

They're all yelling at me!"

Related to her musical constraint is her lack of snappy stage patter. "When I was in London

last year, as I was trying to go to sleep in the middle of the night, I would think of these

incredibly funny things I could say on stage. But when I got up there, I would think, 'I've

already thought that up, so if I deliver it, it's going to sound wooden.' Then I'd say, 'This is

really stupid, standing here with nothing to say.' So I would say it, and because I was

concerned about it sounding wooden, it would sound wooden.

"I've got the reverse problem from a lot of performers," she muses on the couch before the

fireplace, throwing a sweater off her shoulders to reveal a lacy negligee ("I'm not being

seductive," she interjects earnestly; "It's just hot"). "What they do is seal themselves off

from the rest of the world by taking out their need for personal contact on a large crowd,

because really that's less of a threat than relating one to one. I've never been any good at

that, but I'm pretty good at one to one. I do have close friends; I do have romance

relationships."

Her problems are more a reflection of recent insecurities than of an innate fear of

performing. "When I was a little girl, I knew that what singers did was get up and perform.

I'd get real nervous, but I wanted to do it- I wanted to show them that's what I was. The first

time I really sang in public as a teenager, I just got up there on stage and WHAM, there it was.

I just all of a sudden was on fire and wanted to do it, and it really showed." It still does,

especially her physical joy in singing. And recently, since Jagger and other friends have

badgered her into more fully realizing her abilities as a rocker, she's been cavorting more

exuberantly onstage than ever before. When she trotted onstage recently in a Red Sox baseball

cap, red slip and white-with-red-striped track shorts that looked perilously close to hot pants,

and had kicked off her high-heeled shoes for her final rave-up of "Tumbling Dice" and "You're No

Good," there wasn't another woman singer in rock who could touch her.

Of course it's not just her music that has won Ronstadt her success. Even before her 1970

Daisy Mae, Moonbeam McSwine album cover on Silk Purse Linda was regarded as a sex symbol.

Then it was braless bouncing and bare feet; today, it's more sophisticated and complex, though

no less overt. But there are problems in being a sex goddess, and Linda is constantly reminded

of them.

"I love sex as much as I love music, and I think it's as hard to do," she begins- back at the

oven again this time, poking nervously at her rather leaden-looking bread loaves. "I don't know

how good a sex symbol I am, but I do think I'm good at being sexy. The sexual aspect of my

personality has been played up a lot, and I can't say it hasn't been part of my success. But

it's unfair in a way, because I don't think I look as good as my image. Sometimes I feel guilty

about it, sometimes I feel embarrassed about it, sometimes I feel I have to compete with it.

But that's part of the fun, too- that's part of the charade. When you look at somebody like

Jean Harlow real close, she really did have an exquisitely formed face and beautiful hair and

beautiful skin and a real gorgeous figure, and those are things I just don't have. But I don't

think they're essential to being attractive. Sometimes they're more of a handicap than a help.

I think vitality is what is attractive to people. That's why there are a lot of pretty girls

that are kind of boring to look at. If I get a hot romance, my sexuality is likely to work

whether I curl my hair and put makeup on or not. When it's successful and I'm at my shining

best, I like to think of it as sassiness that incorporates sexuality and strength. It's

aggressive without being intimidating. As long as there's strength in my attitude, I like it."

Compared to movie stars of the Harlow era, Ronstadt has far greater control over her own

image. Records are so inexpensive next to films that moguls can afford to indulge their

successful artists, who in turn can dictate not only the contents of their albums but their

cover art and publicity material, as well. But the control can't be complete; journalists,

gossip columnists and the variables of public taste and perception are still too fickle for that.

At the moment, for instance, Ronstadt worries that her image may be getting too sleazy. There's

an undeniable hot-tramp side of her personality- her "hooker streak," as she puts it- as anyone

who saw her recently in high heels, bare legs and track-short/hot pants at the Bottom Line

nightclub in New York can attest. But that's only one part of what she calls her

"multiphrenic" personality, and she worries if people don't perceive the rest. That was why she

bitterly regretted Annie Leibovitz' photos of her last year in Rolling Stone, especially the

candid one of her sprawled on a rumpled bed in a red slip.

"Annie saw that picture as an expose´ of my personality," she says. "She was right.

But I wouldn't choose to show a picture like that to anybody who didn't know me personally,

because only friends could get the other sides of me in balance; only they could get the full

dose. That's why that kind of picture would be called 'intimate.' It defines the word. That

picture implied that when I said girls didn't have to be butch to be equal to the guys that I

meant they had to go to the other extreme and look real dishy all the time. The point is to be

yourself, to be a female person."

Her sex-bomb image leads to other worries: "In Rona Barrett's column I'm always off with

everybody's husband. Some of them I don't even know. I keep saying I wish I had as much

in bed as I get in the newspapers. I'd be real busy. I'd have to make appointments. But the

public could become disenchanted with me abruptly, depending on some aspect of my personal life.

Things like that, you never know."

The basis of Linda Ronstadt's public image remains love in the wider sense, rather than

hard-core sex, and that's a fair reflection of her personality as a whole. "I think I'm a real

seventies person," she offers. "Sixties protest songs always seemed too general to me- and

hypocritical, too, if some guy was singing about mankind just after he'd left his wife and kids.

Maybe I'm a very narrow person. But the experiences that move me deeply are the experiences I

have with other individuals, whether it be friendship or romance. It's always traumatic on some

levels, it's always uplifting on some levels- those are the things I like to express in my music."