MAKING IT IN THE U.S.A

As far as I can tell, Linda Ronstadt's music is pure entertainment. There are no coded symbols, frank autobiographical confessions, or violent eruptions of emotion in it; the stuff is the pop of the seventies.

Now, this is not a profound realization. In fact, it seems entirely obvious.

But ever since the late sixties, when every new record from

Dylan or the Beatles was greeted

as Holy Writ from on High, analysts

of popular culture have been picking over pop music with an intense,

single-minded zeal, searching for

the weighty and the profound. At its

most ambitious, pop music is capable of addressing meaningful

concerns. But the way the analysts

relate to pure pop- music whose

principal raison d'être is the entertainment of large numbers of people-

has little to do with the way the consumers relate to it. Ordinary folks drive to it,

eat to it, make love to it, and in general just enjoy it.

single-minded zeal, searching for

the weighty and the profound. At its

most ambitious, pop music is capable of addressing meaningful

concerns. But the way the analysts

relate to pure pop- music whose

principal raison d'être is the entertainment of large numbers of people-

has little to do with the way the consumers relate to it. Ordinary folks drive to it,

eat to it, make love to it, and in general just enjoy it.

With all these people relating to her music in such a natural way, you would think that Linda Ronstadt wouldn't pay the slightest attention to the articles and reviews that get churned out every time she makes another record. Her most recent album, Living in the U.S.A. (Elektra), racked up more than 2 million advance orders before it was even shipped. She works when and where she wants, and she goes out with the governor of California. And besides, her fans love her. But the cultural analysis bug is highly contagious. Ronstadt's records are beginning to sound like she reads her reviews and takes them seriously.

Ronstadt's most impressive achievement has been the creation of a genuinely contemporary pop

style for the seventies. I'm being careful to avoid using the word rock,

for even though Ronstadt draws heavily from rock or rock'n'-roll sources,

she is neither a rock artist (writes original tunes and projects a persona through a single,

identifiable style) nor a rock-'n'-roll artist (sings with such fervor that personality

completely dominates considerations of content- rocks like a fool).

Instead, she wraps strains of rock, folk, country, and some other brands of American

vernacular music up in an attractive, highgloss package. She is one of a very few

American popular artists, and the only woman, with whom hippies, truckers, housewives,

politicians, and just about everybody else feels absolutely at home. In part,

this broad appeal has to do with her music's lack of specificity. It seems to belong to

everyone while belonging to no one in particular; it packs a certain emotional wallop but

it doesn't force the listener to "relate" to the singer or to any other person in any

prescribed way. Still, one shouldn't underestimate the craft and creativity that go into

making Ronstadt sound as good and appeal as widely as she does.

Ronstadt's most impressive achievement has been the creation of a genuinely contemporary pop

style for the seventies. I'm being careful to avoid using the word rock,

for even though Ronstadt draws heavily from rock or rock'n'-roll sources,

she is neither a rock artist (writes original tunes and projects a persona through a single,

identifiable style) nor a rock-'n'-roll artist (sings with such fervor that personality

completely dominates considerations of content- rocks like a fool).

Instead, she wraps strains of rock, folk, country, and some other brands of American

vernacular music up in an attractive, highgloss package. She is one of a very few

American popular artists, and the only woman, with whom hippies, truckers, housewives,

politicians, and just about everybody else feels absolutely at home. In part,

this broad appeal has to do with her music's lack of specificity. It seems to belong to

everyone while belonging to no one in particular; it packs a certain emotional wallop but

it doesn't force the listener to "relate" to the singer or to any other person in any

prescribed way. Still, one shouldn't underestimate the craft and creativity that go into

making Ronstadt sound as good and appeal as widely as she does.

Peter Asher, Ronstadt's producer, is at least as responsible as she is for the singer's records.

His productions are as clean and spotless as a kitchen in a television commercial, and his

ear for material, abetted by Ronstadt's own savvy in this regard, couldn't be more astute.

The way these two go about putting albums together- a little country, some rock and

rhythm-and-blues oldies, some sensitive songs by contemporary writers, a shiny veneer on

the sound- has been having its effect on other artists for some time now;

and the more platinum albums

Ronstadt makes, the more effect it has. Bonnie Raitt, whose albums have always

been as eclectic as Ronstadt's but who has usually managed to sing with a little more true grit,

is working with Peter Asher now. It might be unfair to anticipate the results of their

collaboration, but one suspects that the sound will be polished, that the material will be

carefully chosen, and that Raitt will emerge with her first hit single. If so, she will

join the list of young women whose albums, despite their individual qualities,

constitute a collective homage to the Asher-Ronstadt formula.

Ronstadt makes, the more effect it has. Bonnie Raitt, whose albums have always

been as eclectic as Ronstadt's but who has usually managed to sing with a little more true grit,

is working with Peter Asher now. It might be unfair to anticipate the results of their

collaboration, but one suspects that the sound will be polished, that the material will be

carefully chosen, and that Raitt will emerge with her first hit single. If so, she will

join the list of young women whose albums, despite their individual qualities,

constitute a collective homage to the Asher-Ronstadt formula.

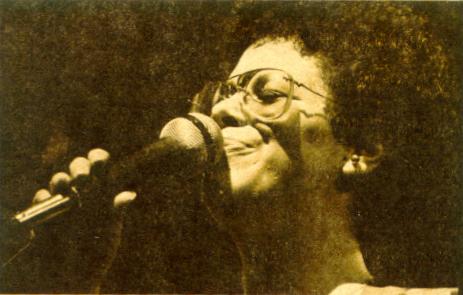

Phoebe Snow- a special

case- has been moving in the direction of Ronstadt, whom she

knows and admires, to the detriment of her own unique talents.

She first made her reputation back

in 1975 with an album of pained,

self-revealing original songs. It was

an album that depended for its effect on the quality of these songs,

on the singing, and on the musical

wizardry of jazz soloists like Zoot

Sims and Teddy Wilson, rather

than on any sophisticated production values. But the albums that followed

dallied with Broadway, the legacy of Billie Holiday, and contemporary pop material

by other writers and were heavily produced. The original songs were fewer and more opaque.

Snow's latest album, Against the Grain (Columbia), at least partially reverses this

trend. It's a performer's album, not a writer's, but it has a single-minded stylistic

orientation- funky, greasy rock'n' roll.

Snow's latest album, Against the Grain (Columbia), at least partially reverses this

trend. It's a performer's album, not a writer's, but it has a single-minded stylistic

orientation- funky, greasy rock'n' roll.

Ronstadt's Living in the U.S.A., which was released about the same time, also leans in the direction of harder rock'n'roll. Theoretically, the move toward rock was a courageous one, but Ronstadt has often had a problem coming to terms with the coldness of modern recording studios, and this is a serious problem for a would-be rocker. Her version of Chuck Berry's "Back in the U.S.A.," which kicks off the album and is its conceptual centerpiece, has a tough, rocking instrumental track, and Ronstadt has everything she needs to make the vocal come alive- a sure sense of rhythm and pacing, admirable control of her voice's many textures, an intellectual appreciation of the song's subtle ironies. But listen to the cut on a good stereo system and it immediately becomes apparent that she sang her vocal in an empty studio over a prerecorded band performance, worrying with every syllable until she got it just so. The essence of rock'n'roll is immediacy. Without it, this and too many of Ronstadt's other rock performances fall flat, crippled by perfectionism.

As for the rest of the album, it works best when Ronstadt and Asher are doing what they know how to do surpassingly well. Such ready-made pop confections as J.D. Souther's "White Rhythm and Blues" and the oldies "Just One Look" and "Ooh, Baby, Baby" will still sound good coming over the car radio ten or twenty years from now because every syllable is just so, because every element fits together seamlessly. They may not have much depth, but in their modest way they're timeless.

The formula Ronstadt and Asher have developed will probably be with us for a long time to come, but Ronstadt herself sounds restless. Living in the U.S.A. seems to have been her attempt, however stillborn, to break the mold, to go for a more genuine, more rocking synthesis. The singer's recent and much-publicized move from Los Angeles to New York will undoubtedly distance her even more from the slick California aesthetic she has seemed to embody for so long. One wonders how much the move had to do with personal imperatives and how much with the more thoughtful criticism of Ronstadt's work one reads in the press. Certainly the perfectionism that's so evident in the most ambitious attempts on Living in the U.S.A. suggests that she is listening to people who think her capable of more than making easy-listening records. One hopes she won't take these people too seriously. Making solid, wellcrafted pop music is preferable to making stilted, pretentious rock.

And what is Ronstadt to do about the critics who now say she is trying too hard?

She'll probably get around to dealing with that, too. For despite her willingness to

be packaged for mass consumption, and despite the potentially baleful impact of her

success on some of her most talented contemporaries, Ronstadt is anxious to succeed as an

artist, not just as a moneymaker. It's impossible to predict with any accuracy what

her change of residence and changing attitudes will bring, but during the next few years

she might just surprise us all.

- Robert Palmer